|

Most galaxies occupy groups or clusters with

from 10 to hundreds of members. Each cluster is held together by the

gravity from each galaxy. The more mass, the higher the velocities of the

members, and this fact can be used to test for the presence of unseen

matter.

.. Early measurements indicated that galaxies in clusters were moving too fast for the amount of matter estiamted from counting the galaxies. This high motion was also detected in other kinematic studies, such as binary galaxies, galaxy rotation and large scale motion of superclusters. This is known as the dark matter problem. |

.. |

.. Up to 95% of the mass in clusters is not seen, or dark. Since the physics of the motions of galaxies is so basic, there is no escaping the conclusion that a majority of the matter in the Universe has not been identified, and that the matter around us is special. The question that remains is whether dark matter is baryonic (normal) or a new substance. |

|

From comparing the mass estimates to the

observed amount of light from galaxies, and from the abundance of light

elements, that there is a problem with the fraction of the mass of the

Universe that is in normal matter or baryons. The fraction of light

elements indicates that the density of the Universe in baryons is only 2

to 4% what we measure as the observed density. The rest of the mass

appears to be `missing', meaning unobserved or dark.

.. Exactly how much of the Universe is in the form of dark matter is a mystery and difficult to determine, obviously because its not visible. It has to be inferred by its gravitational effects on the luminous matter in the Universe (stars and gas) and is usually expressed as the mass-to-luminosity ratio (M/L). A high M/L indicates lots of dark matter, a low M/L indicates that most of the matter is in the form of baryonic matter, stars and stellar reminants plus gas. .. A important point to the study of dark matter is how it is distributed. If it is distributed like the luminous matter in the Universe, that most of it is in galaxies. However, studies of M/L for a range of scales shows that dark matter becomes more dominate on larger scales. |

.. |

.. Most importantly, on very large scales of 100 Mpc's (Mpc = megaparsec, one million parsecs and kpc = 1000 parsecs) the amount of dark matter inferred is near the value needed to close the Universe. Thus, it is for two reasons that the dark matter problem is important, one to determine what is the nature of dark matter, is it a new form of undiscovered matter?, the second is the determine if the amount of dark matter is sufficient to close the Universe. |

|

It is not too surprising to find that at

least some of the matter in the Universe is dark since it requires energy

to observe an object, and most of space is cold and low in energy. Can

dark matter be some form of normal matter that is cold and does not

radiate any energy? For example, dead stars?

.. Once a star has used up its hydrogen fuel, it usually ends its life as a white dwarf star, slowly cooling to become a black dwarf. However, the timescale to cool to a black dwarf is thousands of times longer than the age of the Universe. High mass stars will explode and their cores will form neutron stars or black holes. However, this is rare and we would need 90% of all stars to go supernova to explain all of the dark matter. |

.. |

.. Another avenue of thought is to consider low mass objects. Stars that are very low in mass fail to produce their own light by thermonuclear fusion. Thus, many, many brown dwarf stars could make up the dark matter population. Or, even smaller, numerous Jupiter-sized planets, or even plain rocks, would be completely dark outside the illumination of a star. The problem here is that to make-up the mass of all the dark matter requires huge numbers of brown dwarfs, and even more Jupiter's or rocks. We do not find many of these objects nearby, so to presume they exist in the dark matter halos is unsupported. |

|

An alternative idea is to consider forms of

dark matter not composed of quarks or leptons, rather made from some

exotic material. If the neutrino has mass, then it would make a good dark

matter candidate since it interacts weakly with matter and, therefore, is

very hard to detect. However, neutrinos formed in the early Universe would

also have mass, and that mass would have a predictable effect on the

cluster of galaxies, which is not seen.

.. Another suggestion is that some new particle exists similar to the neutrino, but more massive and, therefore, more rare. This Weakly Interacting Massive Particle (WIMP) would escape detection in our modern particle accelerators, but no other evidence of its existence has been found. |

.. |

.. The more bizarre proposed solutions to the dark matter problem require the use of little understood relics or defects from the early Universe. One school of thought believes that topological defects may have appears during the phase transition at the end of the GUT era. These defects would have had a string-like form and, thus, are called cosmic strings. Cosmic strings would contain the trapped remnants of the earlier dense phase of the Universe. Being high density, they would also be high in mass but are only detectable by their gravitational radiation. Lastly, the dark matter problem may be an illusion. Rather than missing matter, gravity may operate differently on scales the size of galaxies. This would cause us to overestimate the amount of mass, when it is the weaker gravity to blame. This is no evidence of modified gravity in our laboratory experiments to date. |

|

The current observations and estimates of

dark matter is that 20% of dark matter is probably in the form of massive

neutrinos, even though that mass is uncertain. The another 5% to 10% is in

the form of stellar remnants and low mass, brown dwarfs. The rest of dark

matter is called CDM (cold dark matter) of unknown origin, but probably

cold and heavy. The combination of all these mixtures only makes 20 to 30%

the amount mass necessary to close the Universe. Thus, the Universe

appears to be open, i.e. WM is 0.3.

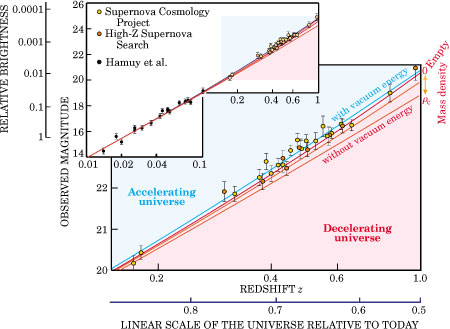

.. With the convergence of our measurement of Hubble's constant and WM, the end appeared in site for the determination of the geometry and age of our Universe. However, all was throw into turmoil recently with the discovery of dark energy. Dark energy is implied by the fact that the Universe appears to be accelerating, rather than decelerating, as discovered by observations of distant supernovae. .. The most direct cosmological observation you can make is to find some standard candle, an object with a known luminosity, and follow its change in apparent luminosity with distance (like watching the headlights of a distant car). The problem is most objects, like galaxies, change in brightness from the past till now. One object which is constant is the brightness of a supernova, but until recently the technology to capture them at high distances was not avaliable. Below is the results of the high redshift supernova project, a unique combination of space and ground-based telescope work. |

.. |

.. This new observation implies that something else is missing from our understanding of the dynamics of the Universe, in math terms this means that additional cosmological constant in Friedmann's equation, L. The implication here is that there is some sort of pressure in the fabric of the Universe that is pushing the expansion faster. A pressure is usually associated with some sort of energy, we have named dark energy. Like dark matter, we do not know its origin or characteristics. .. With a cosmological constant, there are many possible types of Universes, almost any kind of massive or light, open or closed curvature, open or closed history is possible. Also, with high L's, the Universe could race away. |

.. |

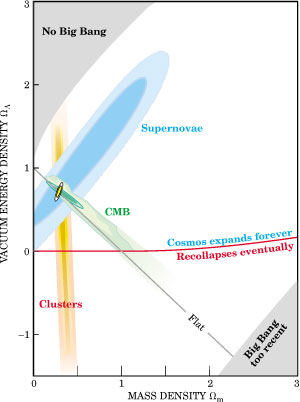

.. Fortunately, observations, such as the SN data and measurements of the cosmic microwave background constrain the possible values for the density of matter and the cosmological constant. The following diagram displays the results and error ellipses for these three observations. The density of matter is constrained by cluster observations to be around 0.3. The flattness of the CMB forces a k=0 Universe, as expected by inflationary cosmology (see next lecture). Lastly, the SN data contrains the value of the cosmological constant. |

.. |

.. SN data gives WL=0.7 and WM=0.3. This results in Wk=0, or a flat curvature. This is sometimes referred to as the Benchmark Model which gives an age of the Universe of 12.5 billion years. .. Is this the end of cosmological work? Unlikely, continued information still flows in on the conditions near the Big Bang. For example, the following is a list of the current models being considered to explain the first moments of the Universe: Quasi-steady state (non-cosmological redshifts), NUT space (microlensing space), Brans-Dicke gravitation (dark energy couples to dark matter and baryons), Godel cosmology (inclusion of shear and rotation), Lyra geometry (2D singularities or domain walls), complex topologies (dodecahedral shaped universe), Cardassian expansion (non-linear Hubble's constant), Quantized everything (particles based on radius of universe), self-creation comsology (no horizons), cosmological synchronization (cosmological factors affect fluctuation processes), backward universe (evolution proceeds to less order). |